The Data Heist

Picture this. It was the summer of 2021. We had been working for half a year on getting our product up and running at the hospital ward where we were piloting our project. The first milestone was getting a functioning ‘whereabouts’ model that could accurately understand what a patient was doing in their room. Things like ‘the patient is in lying in bed’, or ‘the patient has fallen on the floor’.

It took a while for us to fully realise it, but we just didn’t have size and variation of data to create a sufficiently accurate model. We needed more training data, and fast. Enter the ‘data heist’, which admittedly sounds illicit, but I promise you it wasn’t. By the weeks end we had flawlessly gathered a team and pulled off an elaborate plan, all in the knick of time.

The plan:

- Make a script based on the list of actions that we want to detect.

- Find a film set that looked like a hospital.

- Call in actors and volunteers to pretend to be patients and doctors.

- Get the actors to follow the script we made, then film all of this from multiple angles.

- Train our model on this new video data

The catch:

It was the middle of the summer, and we only had a week to get it all done before some key team members were going on holiday.

Step 1: Make a script based on the list of actions that we want to detect.

Training a computer vision model to understand what a patient is doing takes a lot of data. Hospitals can be chaotic and unpredictable, and there are endless ways a patient might behave. From high risk situations, like falls that you can’t afford to miss, to countless ways of lying in bed: On your side, legs curled up, with duvet, without duvet, head raised, feet raised, arms out, arms in, arms under your head. The list goes on. The point is that these aren’t edge cases, these are the realities of how people behave, and we have to make a system that conforms to the people, rather than the other way around.

Up until this point, we had been working with patients who had given their consent for us to record them and label their actions. While we greatly appreciated that these people would help us improve our functionality, we were in the difficult situation where, to detect a fall, you also need to have seen and collected data on multiple falls. And we wouldn’t wish that upon anyone.

This was the genius of our heist idea. Rather than having to wait and film real life situations (ones that we didn’t actually want to happen), we could ask the actors to, for example, lie on the ground in different positions, or move around in the bed in many different ways. Now we could get a much richer data set, and in a much shorter time frame.

So we made a script of all actions that we wanted to understand, making sure to get as much diversity of behaviours as possible.

Step 2: Find a set that we could film our hospital scenes in

This one felt like fate. I wrote to our partner hospital asking if they had a room that we could borrow for filming in for a day or two. And their response was that they actually had a whole ward! They were in the middle of renovating a whole ward, and they could give us the whole thing for a few days. All 15 rooms, along with hospital beds and equipment.

We have always found that having an inside man (in this case the ever-supportive Nykøbing Falster Hospital) allows for projects to go off much more smoothly.

Step 3: Call in actors and volunteers to pretend to be patients and doctors

This one was daunting. We had a week to gather a bunch of people to travel to a hospital 2 hours outside of Copenhagen. Family members? Too busy. Friends? Too far away. Actors? Too expensive. What about extras and background actors? Well that just might work!

So we set about posting gigs on facebook groups and casting sites for actors who wanted to come and pretend to be patients in a hospital. We even called up the local amateur theatre company. Then we crossed our fingers…

Sure enough one by one we got a trickle of phone calls and emails from actors throughout the local area. One lady even promised to bring her nurse-daughter along to help out.

Within two days we had contracts and payment in place, and a group of 20 actors who would come along to the hospital the following week and pretend to be patients. (This included my 88 year old grandma, who lives right around the corner from the hospital). I was impressed by how kind and enthusiastic people were for helping out on a project like this. There really are a lot of opportunities out there if you just ask.

Step 4: Get the actors to follow the script we made, then film all of this from multiple angles.

Finally, the filming days were upon us. We rented a little summer house down by the hospital, and moved the whole company (only 7 of us at the time) down to our new base of operations.

We arrived the day before we needed to film, and quickly scoped the empty ward to work out what we could do with it. We made a waiting room, a canteen, and two film sets. Our team was going to split into two teams, with directors, assistants, ‘doctors and nurses’ and then a few runners who could help out between the two teams. This would allow us to fit more filming into each day.

The film sets were just normal hospital rooms, but we had fashioned a set of camera rigs so we had 8 cameras in each room capturing all the actions from all angles (another way of diversifying the data set). There were already hospital beds, wheel chairs, IV drips dotted around the ward, so we gathered them together and put them in the props room, so we could easily use them throughout filming. I picked up some costumes (patient clothes) from one of the wards. We also blocked out the windows with some cardboard so that we could make a room completely dark as if it was night time, otherwise we might end up with a system that worked really well in the day, but would send false alarms all the time during the night.

Once we had finished setting up and gone through a dress rehearsal, it was time to go back to the summer house and get some sleep before the big days ahead of us.

Lo and behold, the next morning, we found a group of actors waiting for us by the reception desk of the hospital. Every 2 hours a set of two new actors would be waiting for us by the reception desk. I would guide them up to our ward, give them a peak into the rooms we were filming in, and then take them to the ‘business room’ where they would sign a contract and give us permission to use the data for training our model. We had offered a payment for their time as well, so everyone could be fairly compensated.

After this the actor would be given some patient clothes to wear, and we would set them down in the waiting area until the film crews were ready for them.

Once ready the actor would be welcome in, and guided through everything from laying in bed, to walking around with a ‘nurse’. We had arranged for real trainee nurses do come by throughout the day to assist with capturing more technical activities such as pretending to administer medicine, or hoisting actors up in a patient lift and moving them around throughout the room.

We had a lot of fun.

This wasn’t exactly something than anyone involved had tried before, but the slight awkwardness seemed to put everyone more at ease. There was a sense that actors and film crew alike could improvise and figure it out as they went along. Personally I’ve always found these kinds of experiences to be some of the most engaging parts of working at Teton. When we go out of the office to work in the real, physical world. We get to know new aspects of everyones character (for example, who knew that Roland (our lead backend engineer) could play such an eerily convincing geriatric patient?

Anyway, I digress.

By the end of the two days of filming we had collected hours and hours of unique data. Now all there was left to do was…

Step 5: Train our model on this new video data.

And so, our ragtag team had managed to pull off the heist of the century, and I could go on holiday resting easy that we had safely secured the metaphorical bag.

The following week the rest of the team were back in the office, and had started labelling all the fresh new data. The improvement in the detections was undeniable, we had riches beyond our wildest dreams.

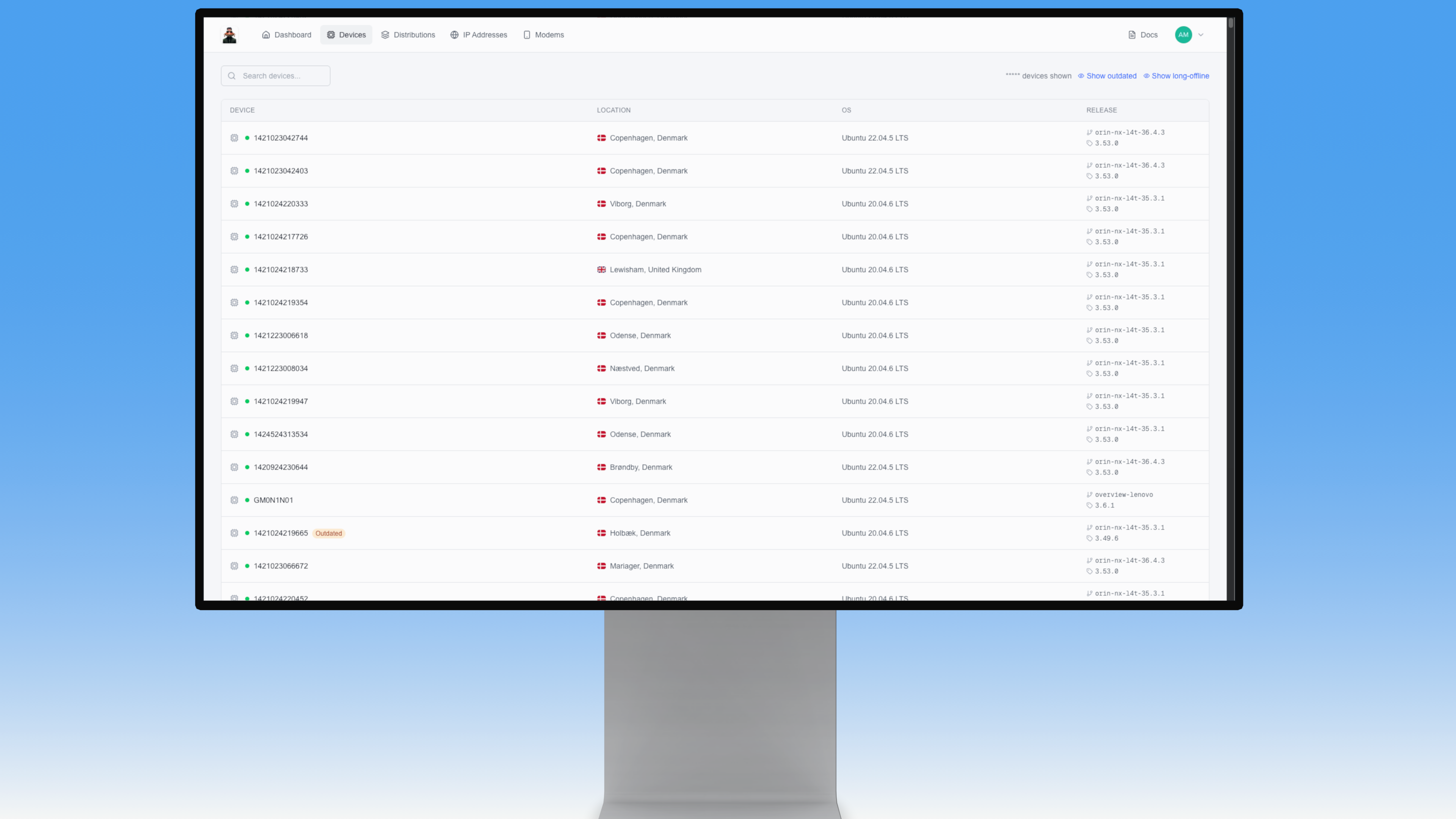

Since then, life has moved on, we’ve released a product that staff use every single day, but the memory of the heist lives on. As I sit here, mysteriously looking out over the city, I can reflect on what could have been: A product that didn’t work, a failed pilot program, a group of frustrated engineers and designers. Looking back, the data heist was one of the most impactful decisions we made in our first year, both in terms of product quality, but also in terms of our own conception of how we could approach problems. In the daring world of monitoring technologies for the care sector, those who dare to walk the walk may find themselves in a story that will be remembered for years to come (or at least they’ll find their story retold in a niche blog post).

The end

.jpg)