From Silicon to Site: Building Secure Sensors for Healthcare

When building new technology, you eventually collide with something unavoidable: the real world. If we want to become the definitive source of truth for care communities, we must be physically present in those communities. That means deploying sensors, the "nervous system" that lets our platform understand activity inside a site and support staff in their work.

At Teton, our product is made of many layers, but everything begins with the sensors we install in patient and resident rooms. They provide the data that higher-level models, workflows, and insights depend on. Installing hardware in such personal, high-stakes environments brings several responsibilities. Devices must blend seamlessly into the environment without drawing attention, but they must also be secure.

This raises clear questions: What does security mean for hardware placed inside these rooms? What protections do these devices need? And how do we ensure that partners can trust the data we collect, and the systems we operate?

For us, that trust starts at the base.

The Threat Model

Before talking about how we secure our devices, we need to be clear about what we are securing them against. This is where the idea of a threat model comes in. A threat model is simply a description of the risks we consider and the assumptions we make about the environment our devices operate in. It guides how we design hardware, software, and operational practices.

Once you place hardware inside a care room, the security conversation becomes very concrete. People naturally ask what the device is doing. How does it work? Can it see me? Can it hear me? Can it track me? These are not devices tucked away in a locked server rack. They sit in someone’s living space, sometimes during the most difficult moments of their life, and we have a responsibility to address these concerns and ensure the device feels safe to be around. Our devices operate in semi-monitored spaces where individuals, visitors, and staff move around them every day. That environment shapes how we think about threats and what we need to protect against.

We assume that someone may get brief, opportunistic access to a device. Maybe a visitor is curious, maybe someone else interacts with it. That kind of momentary access should not be enough to open a device, plug something in, or trigger a mode that bypasses normal protections. At the same time, we cannot completely rule out more capable attackers, people with tools or time, although this would typically indicate a broader breach at the site level. This means that trust must come from the system architecture, not only from the room’s level of visibility.

The supply chain adds another dimension. Every device is built from components that pass through multiple hands, and we rely on external partners for parts of the process and components. A realistic threat model must include the possibility of manipulation during these steps. We need predictable hardware, trustworthy partners, and consistent manufacturing practices.

Because we operate a large fleet of IoT devices, we also need to consider fleet effects. A network is only as strong as its weakest links. We design with the assumption that a single compromised unit must not grant access to any other device, any sensitive data, or any part of the broader system.

Finally, because we operate in healthcare settings, privacy is part of the threat model from the start. Devices should not hold information that could identify people or expose clinical details. Even in a worst-case scenario involving physical access or full compromise, an attacker should not be able to learn anything meaningful about the person in the room.

This may seem like a lot, but taking security seriously also means being transparent about the risks and clear about how we address them.

Our security principles

Once we understand the environment our devices operate in and the potential threats within it, the next step is clearly defining what strong, reliable security should look like.

Instead of viewing security as a collection of individual features or on and off protections, we ground our work in a set of guiding principles. These principles shape how we design and evaluate everything we launch in real life situations. They keep us focused on what truly matters and help ensure our decisions remain reliable and consistent as the product evolves.

Minimize what the device knows

A device cannot leak what it does not have. Our devices are designed to operate without knowing which person they are monitoring, clinical details or sensitive metadata. Keeping the device intentionally unaware reduces the impact of a potential compromise.

Assume physical access is possible

Even in semi-monitored rooms, someone may touch or interact with a device. We approach hardware design with the expectation that brief access can happen, and that security must still be held under those conditions.

Each device as its own trust boundary

A single device should never become a stepping stone into the rest of the system. We design with containment in mind, so that a compromised unit does not cascade into a larger, predictable failure.

Integrate safely

Our devices do not exist in isolation. They operate inside real networks managed by real people, and we must ensure that we never become a source of risk for the sites that deploy us. We work closely with IT teams to understand their environments, follow their requirements, and make decisions that fit their security expectations. Clear communication and collaboration help ensure that our solution integrates safely and that partners always know how the system behaves and what it needs.

Prefer transparency over obscurity

Security does not come from hiding how things work. We lean on open standards, documented interfaces, and external scrutiny where appropriate. This helps us catch problems early and build trust with our partners.

How do these principles shape our product?

The first practical outcome of these principles is how we structure the relationship between the sensor, the computing unit, and the site network.

.png)

A point of confusion we sometimes see is how the sensors actually connect to the network and to our backend. By design, only the computing unit is connected to the site network. The sensors inside the room connect directly to that computing unit and nowhere else.

This means that the sensortraffic stays entirely inside that local loop. It does not leave the room; it does not appear on the site network, and it is never exposed to the internet. In effect, the sensors are isolated from the outside world, which is important because sensors are generally the most sensitive part of any vision-based system. We do not rely solely on the manufacturers we work with. Instead, we treat sensors as components that must be contained and controlled, not as devices to be trusted by default.

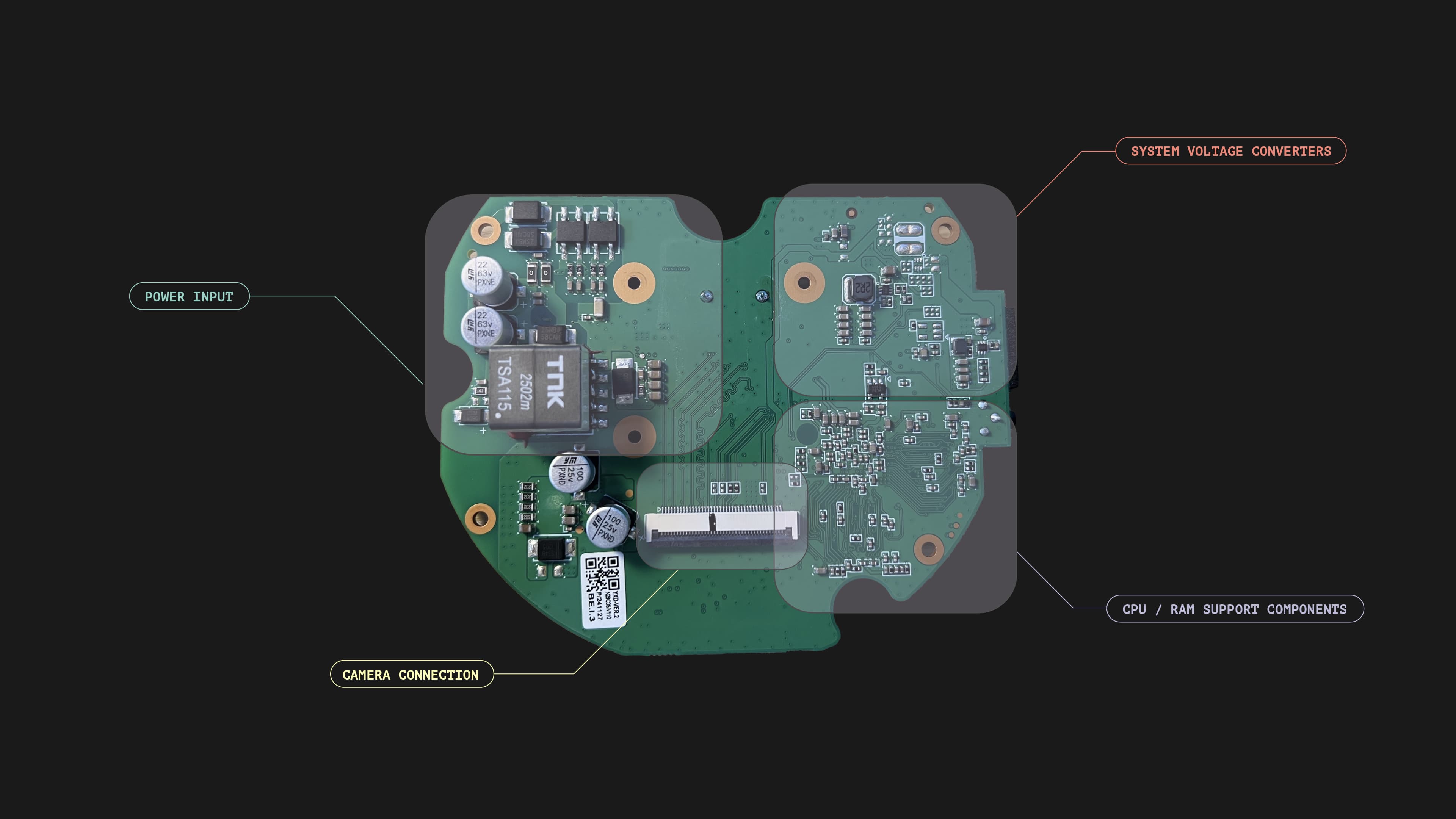

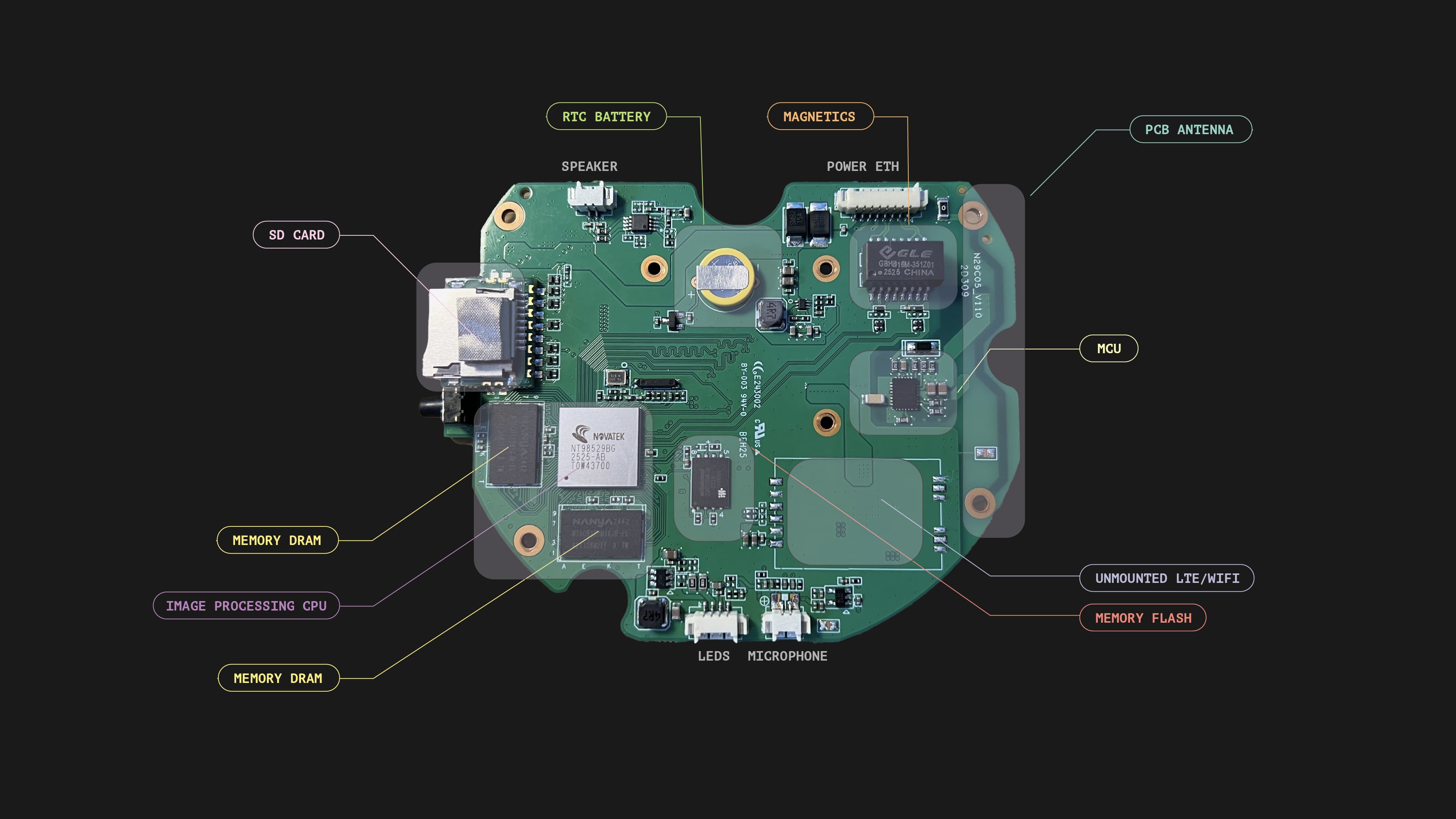

As part of this approach, we also inspect the sensors we use at a hardware level. We periodically disassemble units to verify that they match the expected design and to ensure there are no extra components, radios, or interfaces that should not be there. This is not about distrusting our suppliers. It is about validating the hardware we depend on and making sure that the most sensitive part of the system behaves exactly as we think it does. A simple teardown can reveal a lot, and it helps us maintain confidence in the devices we deploy inside care rooms.

All processing happens locally on the computing unit. The raw feed is analyzed on-site, and only processed data is sent to our backend. At that point, the information does not carry any personal identity or link to personal history.

The device does not know who it is observing. It only knows what it sees in the moment and the output produced by the models running on the computing unit.

How do these principles shape our processes?

These principles also guide the way we build, deploy, and manage our devices. We assemble our hardware in-house using components from trusted suppliers, and we perform our own engineering assessments before anything is put into service. When devices are installed on-site, we work with trained installers who understand the environments they are entering and the standards we expect.

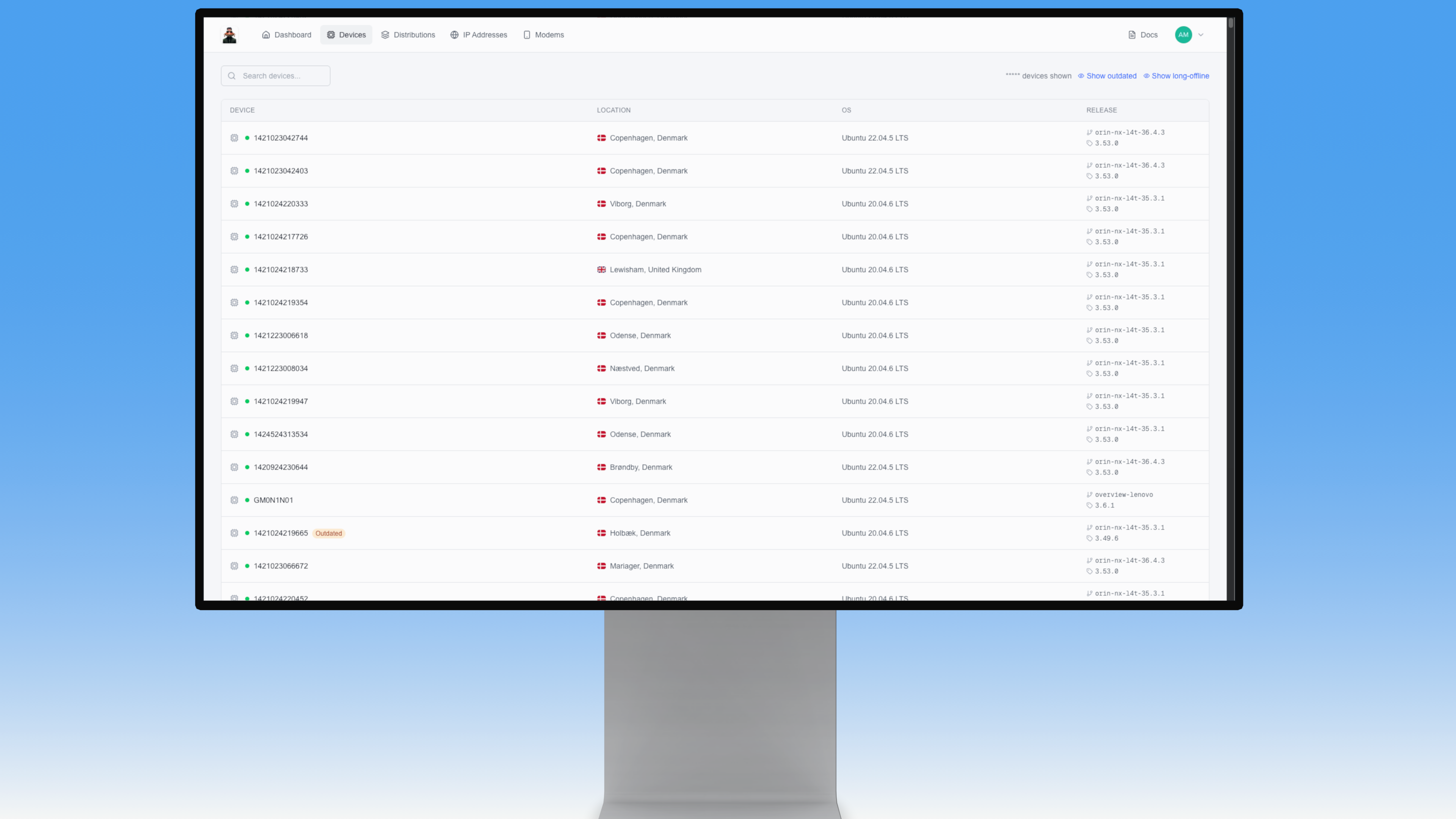

Every device we deploy is managed centrally. Nothing is allowed to communicate with our backend until it has been reviewed and approved. This helps ensure that only known, verified hardware becomes part of the fleet.

Once devices are in the field, we stay in close contact with site IT teams and monitor device behavior as part of our normal operations. If something goes offline or behaves unexpectedly, it generates alerts so we can assess the situation quickly. The goal is not surveillance of the sites themselves, but awareness of whether our system is functioning the way it was designed to.

We also welcome outside input.

We run a bug bounty program and encourage security researchers to reach out if they discover potential issues. Openness helps us improve, and external scrutiny is an important part of building resilient systems. To support this philosophy, we open source our internal fleet management tool. This gives partners and the broader community more visibility into how we handle devices at scale and reinforces our commitment to transparency and trust.

Closing thoughts

Securing devices inside care rooms is not simple, and it should not be. These environments involve real people, real vulnerabilities, and real responsibilities. Our approach is to be honest about the risks, clear about the assumptions we make, and deliberate in the way we design both our hardware and our processes. Security is not a checklist, and it is never finished. It is an ongoing practice that evolves as our product grows and as we learn more from partners, researchers, and the sites that rely on us. By grounding our work in strong principles, validating what we build, and staying open to scrutiny, we aim to create systems that people can trust during the moments when trust matters most.